How does smoking a joint change a joint?

The therapeutic properties of medical cannabis are attributed to its active pharmaceutical ingredients known as APIs, which are primarily cannabinoids. With well over 100 identified, including well-known compounds like tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), cannabidiol (CBD), and cannabigerol (CBG), cannabis presents a diverse array of therapeutic compounds. Additionally, the plant contains over 200 terpenes, with around 20 being the most prevalent, and then a whole suite of flavonoids, esters and others, including sulfur-containing compounds contributing to the chemical makeup.

A recent study by Eyal et al. called Inconsistency in the Composition of the Smoke of a Cannabis Cigarette as Smoking Progresses: Results, Mechanism, and Implications, has tried to break down what happens to the chemicals in a burning joint. This would explain why the start and end of a joint are different; it explores the role heat plays and might even suggest that smoke itself affects the composition of the unsmoked part of the joint.

Previously On Puff The Magic Dragon

Previous investigations into cannabis smoking have mainly concentrated on the hazards of smoking, revealing low delivery yields of cannabinoids in the smoke. However, this study from 2005 shows cannabis cigarettes (joints) are significantly less cancerogenic than tobacco cigarettes. Other studies have shown that up to 50% of cannabinoids can be lost in side-stream smoke, up to 30% destroyed by pyrolysis, and 10% trapped in the butt. Furthermore, smoking parameters such as puff frequency, duration, and volume significantly influence cannabinoid yield. Mixing cannabis with tobacco, a common practice, has been found to increase THC yields, potentially due to differences in combustion temperatures and vapor pressure equilibrium. However, this needs to be investigated further as the adverse effects of tobacco far outweigh the potential increase in THC yield.

Combustion Studies Severely Lacking

Despite the critical role of various APIs in the nature and efficacy of cannabis medical treatment, limited research has focused on the smoking delivery yield and rate of provision of APIs beyond THC. In fact, many regions do not allow medicinal cannabis to be smoked, and in the UK, for example, if you smoke your prescription cannabis flower, you are no longer consuming cannabis ‘legally’. Furthermore, many plant treatments, such as pesticide sprays, which are approved for use on food crops, are also allowed by default to be used on cannabis plants with no data whatsoever on the combustion/breakdown of these compounds – a worrying reality of the medical and commercial cannabis world.

Existing studies have reported total terpene content in smoke and concentration of specific terpenes, but comprehensive insights into the composition of inhaled fractions during cannabis smoking remain elusive. Building on recent findings demonstrating significant differences in the evaporation rates of different cannabis APIs when inhaled through a vaporizer, this study aims to contribute to the understanding of multi-API component compositions inhaled during cannabis smoking. Specifically, the research focuses on the reproducibility of smoking results between portions and the mechanistic explanation of these outcomes. Through these investigations, the study shed light on the nuances of cannabis smoking and its impact on the delivery of therapeutic compounds. The control for this experiment was a cannabis flower which had its THC removed through solvent extraction.

Seeing Through The Smoke

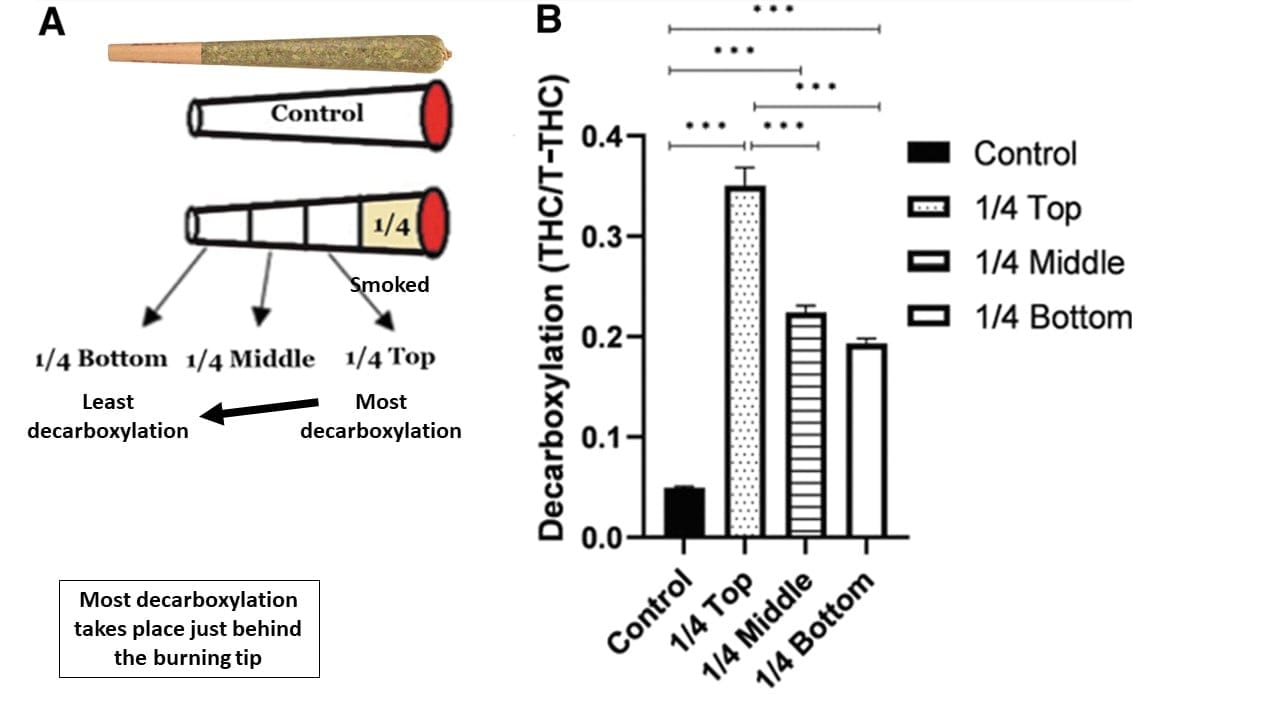

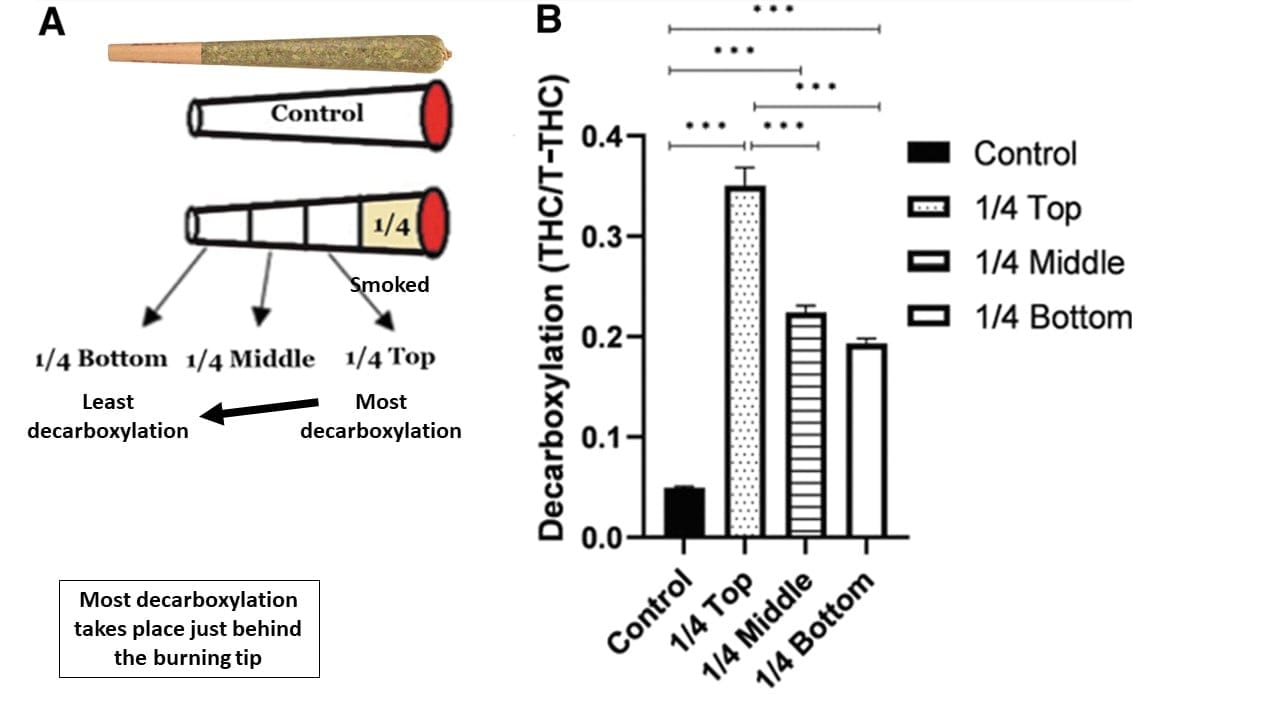

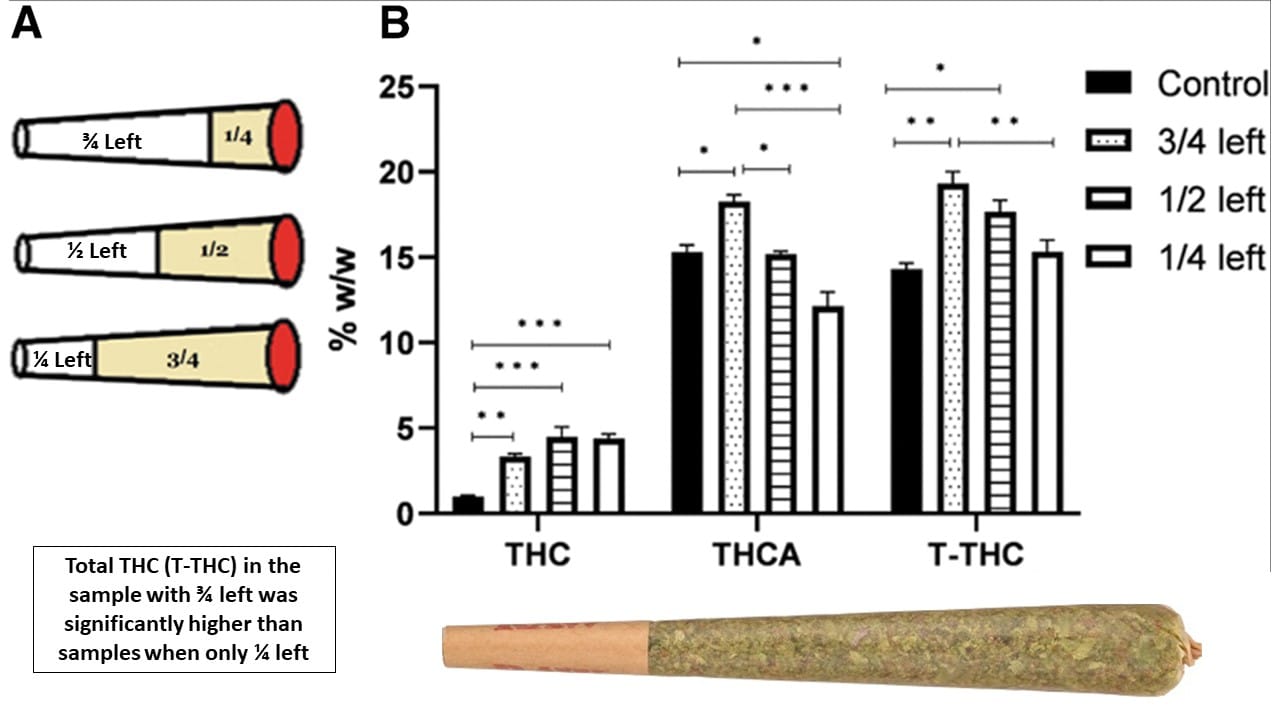

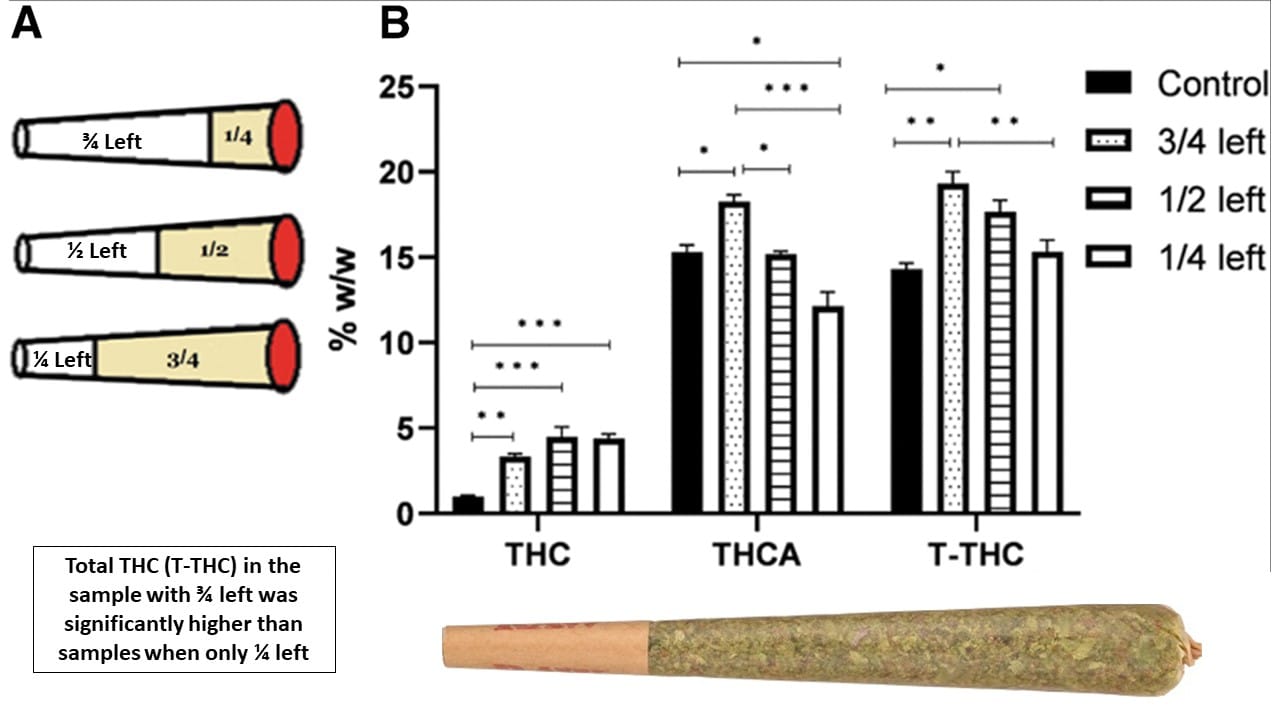

While smoking is a standard method of cannabis consumption, there is limited understanding of the yield and provision rate of cannabis APIs during this process. To address this, the researchers conducted ten experiments using a designated smoking machine to study changes in API content during smoking. The evaluation included analysing residuals from the smoked joint and assessing the composition of the smoke, specifically looking at cannabinoid and terpene content. Initially, the focus was on how decarboxylation, a process crucial for activating THC, varies across different parts of the joint. It was found that the part nearest the lit end of the smoked cigarette underwent the most decarboxylation. Furthermore, when exploring the remaining non-smoked parts of the joint, it was observed that the THC levels in those closest to the lit end were consistently higher than in the control samples. Specifically, the middle and upper-middle sections of the joint showed a notably greater concentration of total THC.

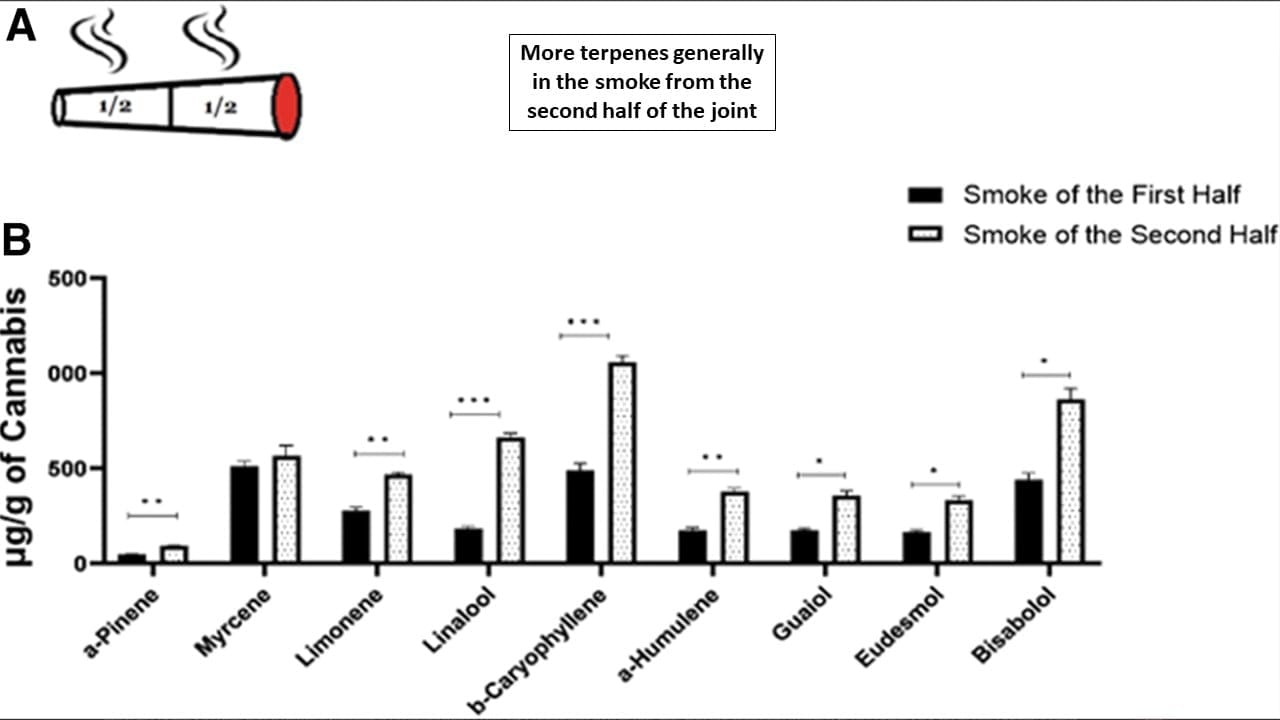

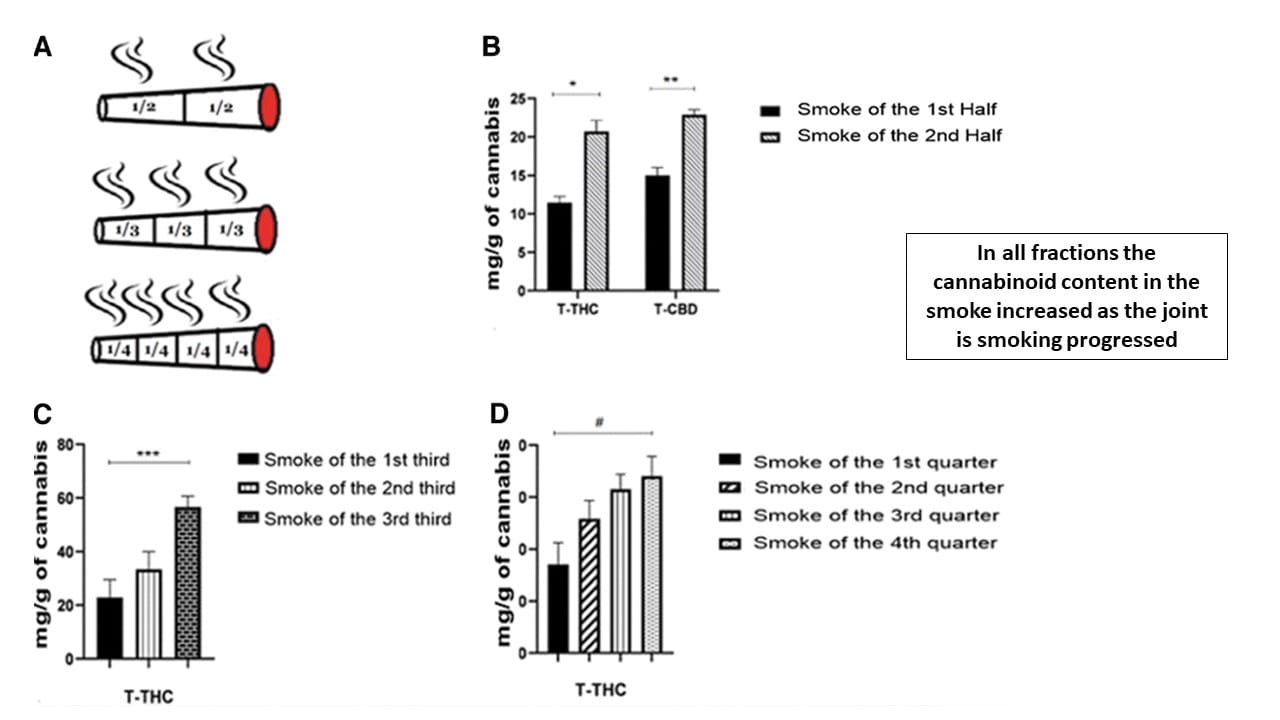

The investigation then extended to the residues after most of the joint was smoked. Here, after ¾ of the joint was smoked, the ¼ left over was not only elevated in THC levels but also certain terpenes like linalool and caryophyllene were found in higher concentrations. A closer look at the terpene profile revealed interesting patterns. After smoking just ¼ of the joint, the remaining lower sections retained higher concentrations of various terpenes compared to the upper sections.

A Smoking Analysis

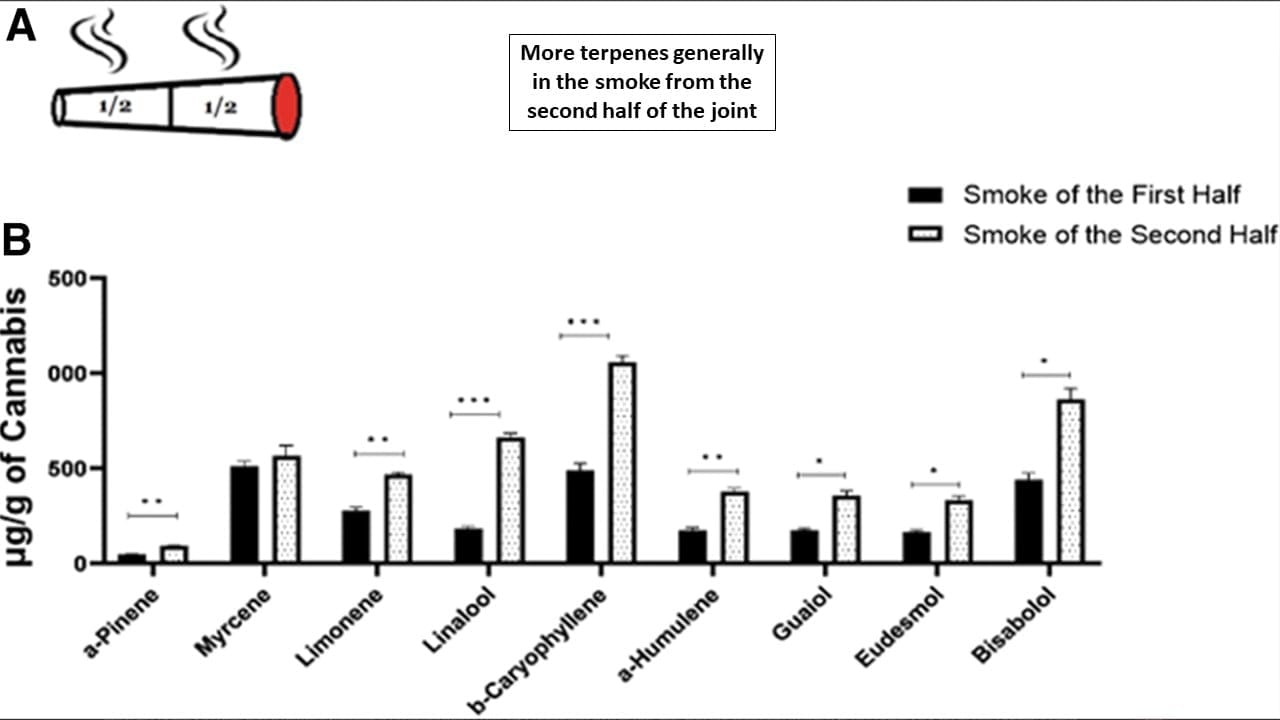

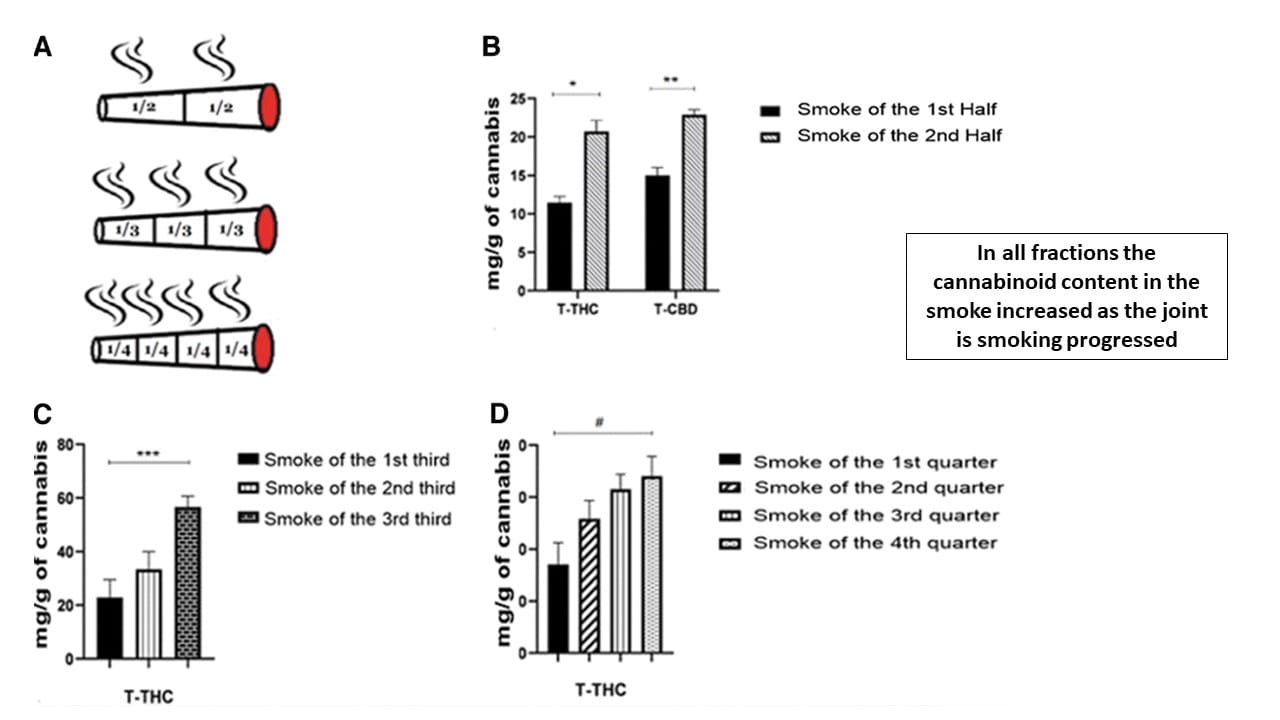

Further experiments compared the cannabinoid contents in the smoke from different segments of the joint. The latter half of the cigarette produced smoke with higher levels of both total THC and total CBD compared to the first half. This part of the study also highlighted increased total THC content in the smoke as one progresses through the joint. When comparing joints made with a mix of cannabis and blank material, the control joints containing only cannabis showed significantly higher THC content. This was quantified as a 28% yield in the control cigarettes, in contrast to a 17% yield in mixed-material cigarettes.

The study also looked at the different sections of the mixed-material joints that affected the cannabinoid and terpene profile in the smoke. Variations were observed, with sections containing a balanced mix of inflorescence showing higher cannabinoid content. The yields of both CBD and THC for these sections were also calculated. The heat from the burning tip decarboxylates cannabinoids in the solid material closest to it (the top quarter), making them active. As smoking continues, the compounds in the latter half of the cigarette are also heated and released into the smoke, leading to higher concentrations in the smoke towards the end of the smoking process. The study provides a comprehensive understanding of how smoking affects the distribution and concentration of essential compounds in a cannabis cigarette, offering valuable insights from both scientific and medicinal perspectives.

The Mechanism – Chemical Changes

The study's findings show a mechanism for the transfer of cannabinoids and terpenes from cannabis into smoke. This process involves partial degradation of cannabinoids, their decarboxylation, evaporation, and eventual re-evaporation into the smoke as the heat source approaches – more going on than one would think! A similar mechanism is observed for the larger, more complex sesquiterpenes and sesquiterpenoids, except they do not undergo decarboxylation. With lower boiling points, the smaller monoterpenes evaporate earlier and condense less, leading to their earlier presence in the smoke. This mechanism explains the dynamic changes in the composition of the joint and its smoke as smoking progresses. Notably, it affects the delivery yield of APIs like THC and is even correlated with CBN formation.

A crucial outcome of this study is the non-uniform delivery of cannabinoids and terpenes during smoking. The concentration of these compounds increases with each puff, meaning that the latter half of a joint can deliver a significantly higher dose than the first half. Terpenes, particularly monoterpenes, are inhaled before cannabinoids due to their faster evaporation and lower boiling points. This phenomenon also occurs in vaporizers and results in higher terpene delivery yields due to their reduced degradation and quicker movement away from the heat source.

Conclusion

The study highlights a distinct difference in the delivery and composition of active ingredients between smoking cannabis and using cannabis oils or extracts. In oils, monoterpenes are often lost during processing, contrasting with their presence and behavior in smoked cannabis. These insights are vital for understanding the pharmacological effects of cannabis smoking and can inform both healthcare professionals and users alike.